Emma is an eight year old girl who lives in Bristol with her mum and her two older sisters. Dad is not at home and she’s had a series of disappointments around mum’s short term (and often suddenly disappearing) boyfriends who she has often got to like. She’s your average kind of eight year old: behaving ok at school generally; seems really happy with her friends; likes gym and horses.

However, that’s where Emma’s average kind of life stops. You see, Emma likes to hide a secret - she’s actually terribly anxious. There’s been some scary stuff going on in her head, she doesn’t really know why it started, but it’s making it hard to concentrate in school. She’s getting told off for not concentrating, her work is slipping, she’s crying some days and won’t say why, and she says she feels like no-one understands her. Her mum says Emma’s not sleeping well at home and that she is beginning to stop spending time with her friends.

Mrs Jones at school is deeply worried about Emma’s overall sadness and her change in behaviour along with her lack of homework but nothing school have put in place seems to help. Emma’s mum is really worried about Emma too but at a loss on how to help. Every time they try to chat it ends up in a screaming match with one of them crying.

Mrs Jones asks me to come and work with Emma. Over a bit of time we get to know each other. Emma likes being in the playroom because she can just be ‘her’. She doesn’t have to talk about things that are bothering her, and she discovers she loves telling stories in the sand tray with the miniatures.

Over several weeks Emma tells me stories in the sand tray, I notice things and wonder about them, giving her an opportunity to respond if she wants to. As she begins to trust me, she shows me a story in the sand that explains a lot about her anxiety. With some support she goes on to try different endings to the story out in the tray. She tries out lots of different endings, often going back to one or two favourites. By noticing where things are in the tray, she begins to think about the roles the different people play in the story and what she can change for herself. Sometimes she even tries out being other people, exploring why they feel and behave like they do.

Towards the end of the term I meet with Mrs Jones and Emma’s mum. They notice Emma is seeming happier and coping much better. The classroom is a happier place for everyone now and her friends have stopped worrying about Emma crying in the middle of lessons. I explain Emma is now showing me she’s ready to finish with play therapy by how she’s playing in the sessions.

We decide to end therapy the following half term, so Emma and I work towards a positive ending for the next six weeks, playing with things for the last time, doing special ending activities and finishing with a ‘party’. This is the first time in a long time Emma has had a positive ending and she enjoys the celebration (especially the doughnuts!).

Whilst you might have worked out that Emma isn’t her real name and that I might have glossed over some of the details, the bones of this story are true.

The data that follows is absolutely true and represents genuine results for one child.

How is progress measured in play therapy?

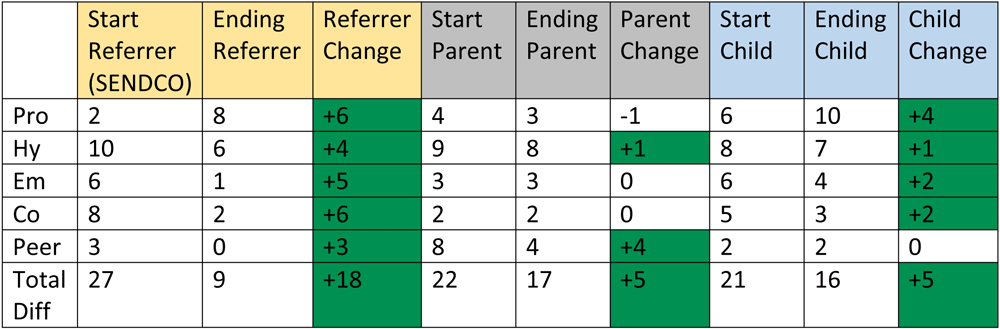

As a play therapist, I use Goodman’s Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to help look at improvements for a child across the therapy sessions. This is a tried and tested questionnaire used by a lot of mental health practitioners. It covers five areas of assessment:

Strengths

- Pro (Pro-social) – a measure of the child’s positive social abilities.

Difficulties

- Hy (Hyperactivity) – a measure of the child’s hyperactive traits

- Em (Emotional) – a measure of how the child manages their emotions

- Co (Conduct) – a measure of the child’s positive behaviours

- Peer – a measure of how the child manages peer relationships

- Total Diff – the total difficulties score (out of 40).

Each area is out of a score of 10. For pro-social scores, the higher the score the more positive outcomes, for all the difficulties, the lower the score, the more positive outcomes.

The SDQ was completed at the beginning and the end of therapy and the results compared. This is done for each client. If you want to know what the questions were, the SDQ can be found online, or you can ask me for a blank questionnaire.

These are genuine results for an actual client who came for 28 sessions of play therapy.

To make it easy, if there has been a positive change, I have highlighted the area in green. As you can see, the child’s scores vary depending on the person doing the form and whether it is home or school related, but a positive change has been made in each person’s view, with the biggest impact being at school. (For this child, the biggest area of concern was around behaviour in school and anxiety, just like ‘Emma’.)

I hope this illustrates for you the dramatic impact play therapy can have for a child and the benefits that it can bring to the classroom by positively impacting just that one client.

I’d welcome the opportunity to support any child or young person that you know who is having a challenging time (for whatever reason). If you’re thinking of a specific child and wondering if play therapy can help, the answer is almost always, ‘Yes!’.

If you have any questions, please feel free to drop me an email: